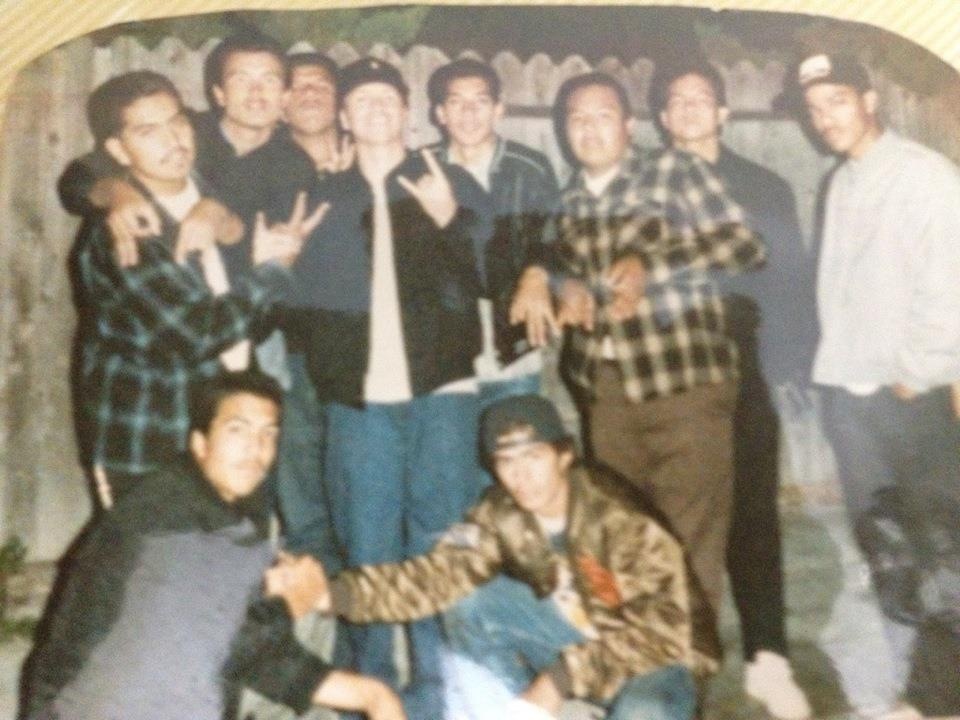

Vista Homeboys Gang Members Victims

What happened to the “gangbanger,” the figure who ruled hip-hop — and, seemingly, the streets of America’s cities — from the late 1980s to the end of the millennium? Andrew tanenbaum sistemas operativos modernos pdf reader gratis. Americans projected their racial and social anxieties onto this figure, inflating him into a “superpredator,” fuel for the tough-on-crime policies of the ’90s.

By the turn of the century, though, the gangbanger’s power waned in our imaginations, drained by the exploitation of the entertainment industry and by the fact that so many actual gang members had been swept into prison. No place seemed to epitomize the “gangsta” lifestyle more than Los Angeles, with television and movie portrayals of mostly black and Hispanic gang members transforming Southern California’s laid-back image into one of racialized terror. There was a reality behind the representation, of course — desperate young people who sometimes caused great harm to others and to themselves, and who might have been only dimly aware of the larger forces pushing them: deindustrialization and globalization disrupting blue-collar paths toward the middle class; the interwoven interests and cynicism of the war on drugs that set many young minority men up to fail; the racial tensions between the police and urban residents. The photographer Joseph Rodriguez arrived in Los Angeles immediately after the 1992 riots that erupted when four white police officers were acquitted of violating Rodney King’s civil rights. Rodriguez documented the lives of gang members, starting in South Central Los Angeles and eventually arriving in Boyle Heights, a majority Mexican-American district on the East Side, which was in what the Rev.

Vista gang drug suspects called violent. JO MORELAND - Staff Writer. Officers were about to raid it as they dismantled an alleged heroin ring involving members of the Vista Home Boys gang.

Greg Boyle, a Jesuit priest and the founder of the gang intervention organization Homeboy Industries, called the “decade of death.” Mr. Rodriguez spent several years on the project, mostly in a neighborhood in the heart of Boyle Heights called Evergreen. The portraits of gang members that emerged were the opposite of the monstrous images in the news media. Yes, there were guns and tattoos, but there was also family, in spite of — sometimes amid — the violence. The photographs captured relationships between mothers and fathers and children and siblings and extended relationships. In 2012, when Mr.

Rodriguez returned to Evergreen to see what had become of his former subjects, gang members were largely absent from the streets. This was partly an effect of a policing strategy in which district attorneys obtained court-ordered injunctions prohibiting gang members from appearing in public together. Some “veteranos” were still languishing in prison. Others had died, victims of violence or drugs. 1993: Steve Blount, one of the few African-American members of the Evergreen gang, left, with his son, Steve Jr. Was killed in a gang-related homicide in 1998. JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ Not everyone had disappeared, though.

Steve Blount, an original member of the Evergreen gang and one of the few African-Americans in Latino gangs, was still around. Rodriguez’s early photographs, Mr. Blount appears as a wounded warrior, addicted to heroin and enduring one loss after another — the deepest when his son Steve Jr. Was killed in a gang-related homicide in 1998.

The father had barely gotten clean when he buried the son. “I cried every day and every night,” Mr. “I woke up every morning crying, asking God when it was going to stop.” Later, he buried his wife, Chris, a fellow addict who died of liver disease. With the pain came the realization that his life was also on the line. “I could have been dead — through gang violence, overdose,” he said. “The fact that I’m still here, I know he has a plan for me.” When I met him last summer, Mr.

Behind the barrel latch and the front of the frame is '209' and under the barrel is '09'. Walther p38 value serial number. Above the trigger is an eagle over '88' and behind that are 2 grind marks.

Blount was living in comfortable retirement in a high-rise building on Bunker Hill, in downtown Los Angeles. From his apartment on the 29th floor, he had a panoramic view of the city, including the rapidly crowding skyline of downtown and the gentle rise of land east of the Los Angeles River — Boyle Heights. He still crossed the bridge to the old neighborhood several times a week to check in on family (he has seven grandchildren and one great-grandchild). But even if he wasn’t at risk of repeating his own history, he still felt as if he was shuttling between worlds. “For me to come over the bridge is like a double life,” he said. 1993: Mark Olvera hanging out with Evergreen Homeboys in Boyle Heights.

JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ 2016: Mr. Olvera with his wife, Veronica. JOSEPH RODRIGUEZ FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES. Then there are the survivors who seem much closer to the edge, like Mark Olvera, who was barely a teenager in 1992. When I met Mr. Olvera at his wife’s family’s house, he was dressed very much in ’90s “homeboy” gear — backward baseball cap, gold chain, T-shirt and shorts, and with plenty of visible tattoos, including a prominent “EG” (for Evergreen) on his temple.